- From: <scsankaran@gmail.com>

- Date: Sun, 29 Aug 2021 22:29:15 -0700

- To: "'Sandro Hawke'" <sandro@hawke.org>, <public-credibility@w3.org>

- Message-ID: <03d701d79d5f$f9833ae0$ec89b0a0$@gmail.com>

I feel this example, while valid, is peripheral to the central problem.

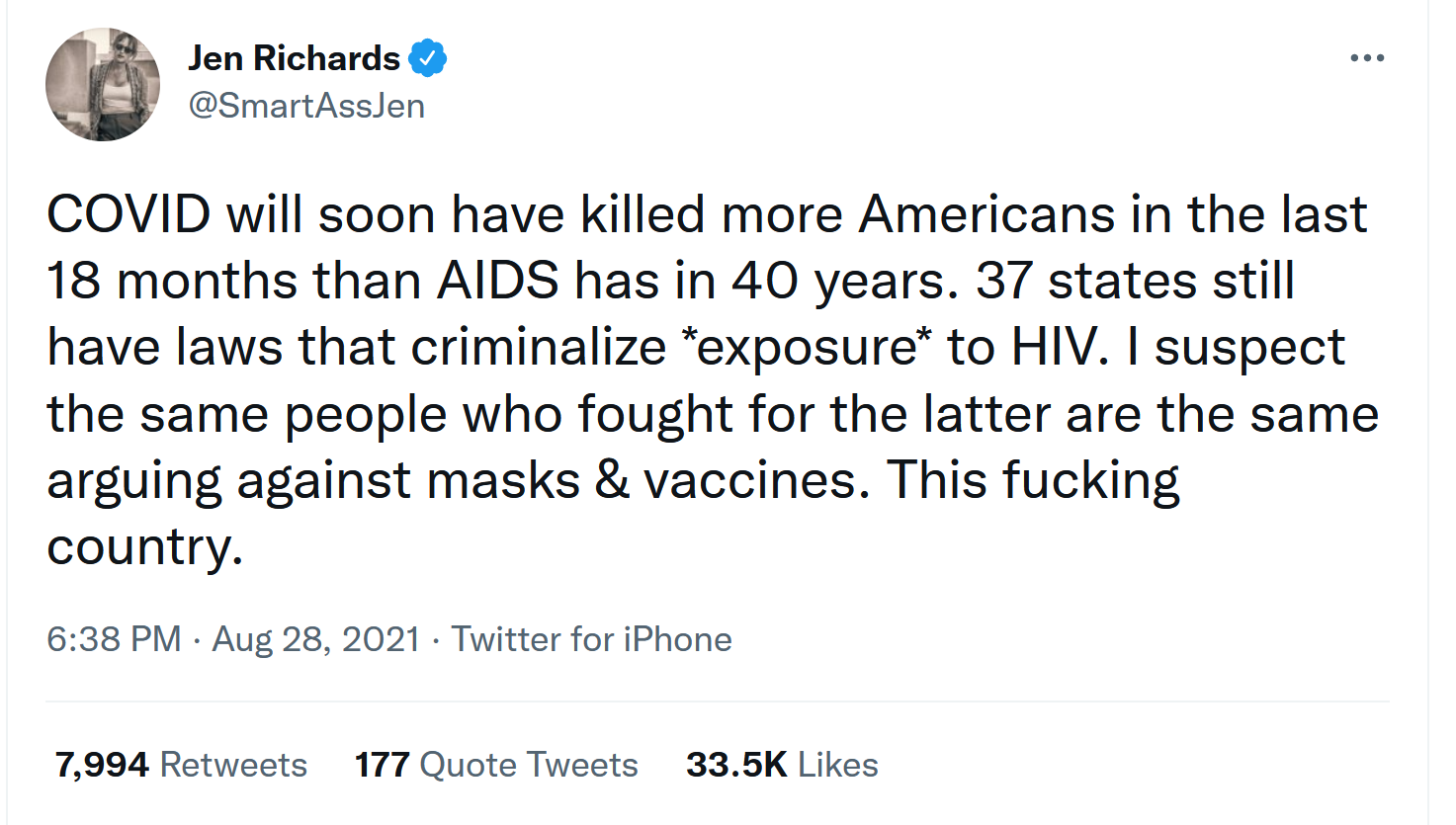

Just numerically, the misinformation problem is to some degree about journalists and readers of institutional journalism but to a vastly larger degree about the millions of casual information broadcasters and consumers on social media and messaging that form the information supply chain. See the recent example posts below that came into our platform. Credibility signals need to surface the reasons for a consumer to be anxious (or not) about these posts below at the point they encounter it. These posts were seen by tens of thousands of people.

The sort of credibility signals we’d care about to solve this problem are very different than the ones being discussed in this email thread. This can’t be a discussion about awards won, or anything you might use to rate an established journalism organization. Ratings such as those done by NewsGuard, Media Bias Fact Check, etc begins to provide some value, but barely so, in this situation.

https://twitter.com/ClayTravis/status/1429174503930613764

https://twitter.com/SmartAssJen/status/1431793390224429056

From: Sandro Hawke <sandro@hawke.org>

Sent: Sunday, August 29, 2021 7:12 PM

To: public-credibility@w3.org

Subject: Re: A Credibility Use Case: Lessig v New York Times ("Clickbate Defamation")

One practical bit out of this is in the menu of justifications behind a human-assigned credibility score, people can downgrade the NYT for Harmful Misleading Headline and point to this as an example. Another applicable menu item would be Slow To Issue Corrections. NYT should IMHO lose some points on both counts.

If there were a system actually keeping a tally, they MIGHT start to care about their credibility decreasing from this kind of behavior.

Of course, among the masses, their credibility is going to hinge on their reporting around US Presidents, I expect; but my persional credibility network will steer clear of that kind of thing, and hopefully yours will to, ... and maybe the Times will care about that eventually.

-- Sandro

On 8/29/21 9:10 PM, Bob Wyman wrote:

Sandro wrote:

it's perhaps the kind of situation where ANYONE willing to spent 30 minutes hard work can evaluate it.

I chose the Lessig v NYT example, in part, because it is so easy to evaluate. In fact, the New York Times' own defense was to say that anyone who actually read the article would realize that the headline was inaccurate. The problem here is that, given the New York TImes' reputation for credibility, few people will actually question the headline's accuracy unless some signal can be attached to it to indicate that further evaluation is needed or, at least, that it is controversial. To amplify your Alice & Hitler example: It's as though a headline said: "Alice likes Hitler," even though she's quoted in the article's paragraph 25 as saying: "I hate Hitler, but I like his style of painting." While we might question Alice's aesthetic sense, there is no reasonable way to go from her statement to the headline's clear meaning. But, given that the quote is in paragraph 25, few readers will discover the contradiction on their own. Most readers will forever think of Alice as someone who likes Hitler and may remain comfortable with that belief because it is based on statements by the highly credible New York Times. ("Who am I to dispute what the NYT has written?") Had the claim been made by some other source, many readers might have either ignored it or questioned it. In such cases, credibility is a problem since it discourages readers from questioning statements.

bob wyman

On Sun, Aug 29, 2021 at 8:37 PM Sandro Hawke <sandro@hawke.org <mailto:sandro@hawke.org> > wrote:

Interesting scenario. A few thoughts.

This is not low-hanging fruit. Evaluating contradictions between credible sources, like this, seems like harder territory to address than some common cases like: a source with no obvious credibility rating, so people end up believing it because it says something they like or uses a nice layout.

But maybe it's not that hard either. The easy thing about this is that it's perhaps the kind of situation where ANYONE willing to spent 30 minutes hard work can evaluate it. Lessig's argument is that the NYT headline and lede are dangerously misleading summaries of his article and the interview. No special information or access or skill is necessary to evaluate Lessig's claim that the NYT got it wrong; just read the article and interview and think a little. That kind of thing can be sort of crowd-sourced. It's not like a public health claim or a mystery.

It's quite hard among self-contained fact-checks, though, because the text has some nuance and the topic is extremely sensitive. It's like if Alice makes a false derogatory statement about Adolf Hitler, then who wants to wade into the muck, fact check her, and get branded a Hitler apologist? And then if her argument required some nuance, ... it's a total mess.

On the mechanical issues:

It's clear to me we need a credibility layer independent from the content layer.

When you're viewing content from X, you need independent annotations and filtering based on signals from your whole credibility network, beyond the control of X.

Ways this could be done:

1. When you're getting your content through social media, the credibility layer can be implemented by the social media platform. I expect social media vendors will be happy to do this once the system is proven to work well but not until then.

2. When you're getting your content through a browser, the credibility layer could be implemented in a browser extension for now and eventually in the browser itself. I think browser vendors would love to do this if the system is proven to work well, but not before then.

3. The website for X *could* provide the credibility layer branded as a neutral 3rd party service that they swear they wont tamper with. I think this is more likely for product vendors than news vendors. X could be a manufacture of Widgets, and they want you to use your credibility network to see that people generally have a great experience with X's Widgets. I think it could also work for news sites, though.

I think the most promising deployment strategies are via (1, above) finding a small social media platform that's interested in making this their distinctive feature, and via (3, above) finding some high traffic sites who are very confident of their credibility rating among people who know them and want to spread the word to others.

-- Sandro

On 8/29/21 5:34 PM, Bob Wyman wrote:

Many think that reliable credibility signals will be useful in addressing the problem of misinformation. But, how do credibility signals help, or hurt, when one highly credible speaker accuses another highly credible speaker of spreading misinformation? Can credibility signals make it harder to combat misinformation?

Some context: On Sept 14, 2019, the New York Times carried an article discussing a medium.com <http://medium.com> post written a few days earlier by Lawrence Lessig. While the body of the article summarized Lessig's arguments with reasonable accuracy, its headline inaccurately described Lessig's position and did so in a way that Lessig believed caused him significant and lasting harm. (For context, see: https://clickbaitdefamation.org/ ) Lessig asked for a correction, but the New York Times, for quite some time, refused to act, saying that anyone who read the entire story would realize that the headline was inaccurate. Lessig argued that most people would believe that the headline was accurate, since the NYT is highly credible, and that most who saw the headline wouldn't read the entire article. Eventually, the NYT backed down and made a correction to the online story.

The New York Times is widely considered to be highly credible. It has been publishing for a long time, it has won thousands of awards, and can present many other indicators of credibility that could be captured in signals. Lawrence Lessig, a law professor at Harvard, co-founder of CreativeCommons.org, winner of many awards, and once presidential candidate, is also able to present many positive credibility signals. Yet, Lessig and the New York Times are in conflict. In this case, not about an article, but just the article's headline.

Given the Lessig v NYT controversy, how do credibility signals help or hurt the ability of third-party readers to correctly identify misinformation? How would credibility signals have helped limit the impact of the misinformation in the New York Times' headline? Also, while Lessig was able to mobilize his considerable public reputation and spend a great deal of effort and expense in combating the NYT, we must wonder if someone without his many positive credibility signals would have found it dramatically harder, if not impossible, to either defend themselves or convince the NYT to correct the headline. When a highly credible source spreads misinformation about someone whose credibility can't be well established, should credibility signals be considered harmful or counter-productive?

Given the web as we know it, Lessig was able to rebut the NYT article by writing a 3,500 word piece on medium.com <http://medium.com> . Lessig also coined the term "Clickbate Defamation" and created a website devoted to it. Further, he contacted the New York TImes, he was interviewed by a variety of other news organizations, and he created a podcast series to lay out his case in detail. He also filed a legal suit for damages against the New York Times. Of course, even with all that effort, only a tiny fraction of those who read the NYT piece ever became aware of Lessig's determined and voluminous rebuttals. His credibility remains severely challenged in the opinion of many readers of the original story who never saw the follow-up. Had Lessig fought less, or been less well-known, it is quite possible that the correction would not have been made. The New York Time remains, of course, considered by many to be a credible publisher.

There are a couple interesting "mechanical" issues here:

* While the New York Times would be likely to present, embedded on its own website, a great many signals attesting to their own credibility and to that of their writers, they are unlikely to be as vigorous in presenting similar signals concerning the many subjects of their writing. Thus, within the context of any story, the signals are always likely to be very biased towards the writer or the publication. Is a reliance on one-sided, self-asserted credibility signals a problem that should be addressed? Should there be a way to "inject" off-site, but relevant, credibility signals into the readers' context? If so, how?

* Unless the New York Times provides for comments (they only do so on some stories), any rebuttals of their articles, or challenges to their credibility, are likely to be seen by only a tiny percentage of those who read the rebutted articles or statements. Even when comment sections are provided, the NYT moderates those comments, controls their presentation, etc. Thus, it is likely that even if Lessig had been able to write a comment on the NYT site, few readers of the headline, or even of the full article, would have seen the comment. (Note: Annotation systems could help here, if more widely used.)

Should credibility signals be useful in a case such as the Lessig v NYT controversy? If so, how are they useful? What is their role? If they are not useful, or are counter-productive, what is the value of credibility signals? Can the utility of credibility signals be increased by some change to their design or implementation?

bob wyman

Attachments

- image/png attachment: image001.png

- image/png attachment: image002.png

Received on Monday, 30 August 2021 05:30:07 UTC