- From: Michael Herman (Trusted Digital Web) <mwherman@parallelspace.net>

- Date: Sat, 11 Oct 2025 07:01:36 +0000

- To: Daniel Hardman <daniel.hardman@gmail.com>, Manu Sporny <msporny@digitalbazaar.com>

- CC: "public-credentials (public-credentials@w3.org)" <public-credentials@w3.org>

- Message-ID: <MWHPR1301MB2094BB232CB391A1B0087AFEC3ECA@MWHPR1301MB2094.namprd13.prod.outlook.>

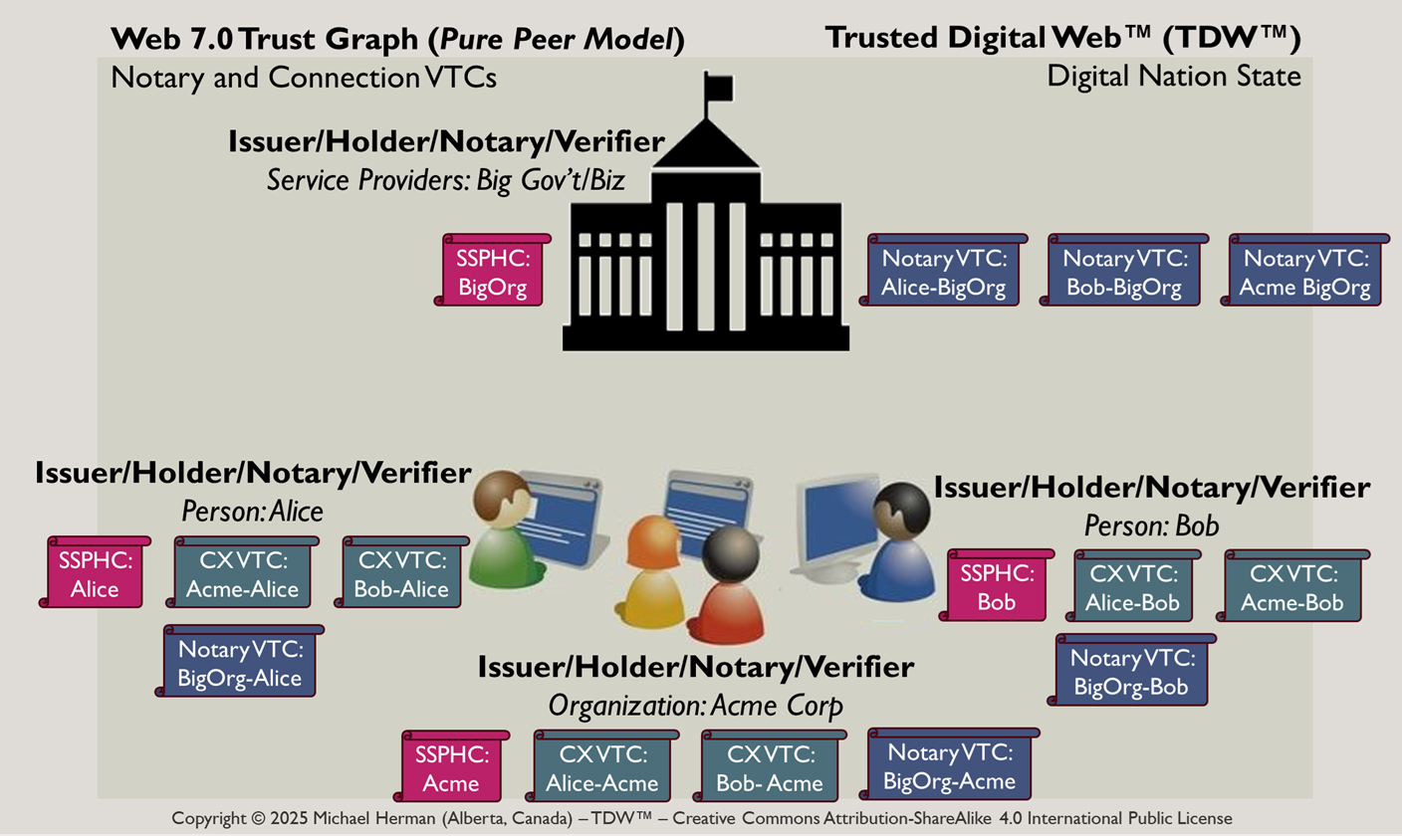

RE: I think it is dangerous to build an ecosystem where proof of personhood is largely assumed to come from governments. In a community/ecosystem of 3 people (Alice, Bob, and Charlie), why would need/want an FPP Overload? …the latter being my term for Big Government/Big Companies that issue credentials. FPP as described in the WP does scale (down). ABC should be able to select one of themselves to be the Notary for any credential issued by the other two parties. This scales from 1-infinity. Lastly, VRCs should be generalized to become Verified Trust Credentials (VTCs) for each and every type of relationship: transactions, connections, issue/notary-holder relationships, etc. Furthering the need to do away with Overlords. [cid:image001.png@01DC3A4A.961483B0] Michael Herman Web 7.0/TDW™ From: Daniel Hardman <daniel.hardman@gmail.com> Sent: Sunday, July 20, 2025 4:40 PM To: Manu Sporny <msporny@digitalbazaar.com> Cc: public-credentials (public-credentials@w3.org) <public-credentials@w3.org> Subject: Re: When Technical Standards Meet Geopolitical Reality In re-reading my response, I see that the words "naive" and "terrifying" are pretty harsh. I want to clarify that I am not impugning people or motives here -- only a particular idea that is an oversimplification of the paper about personhood credentials. And I would like to share an experience so that my strong words have some softening context. Many years ago I adopted two beautiful children from Haiti. My wife and I flew into Miami from Port-au-Prince late in the evening, and made our way to the immigration checkpoint, hands tightly clasping the hands of these two little kids who spoke a different language from us. I carried in my hand a packet of papers that was too precious to entrust even to a carry-on -- the dossier that included birth certificates, visa applications, proof of adoption, DNA tests, notarized translations, attestations from the Haitian and US embassies, and so forth. The packet included originals of these artifacts, plus certified copies. At the checkpoint, I presented these papers to a uniformed officer. He interviewed me briefly, then took the papers back to his desk to run through a checklist. After about 5 minutes he came back and said, "Congratulations, and welcome to the country." However, he made no move to return the papers to me. I thought this was an oversight and gestured to the stack of papers. "I need to have those back." He shook his head. "No, we keep those," he asserted confidently. I felt my heart drop. I said to him, "You keep the copies, but I take the originals." He shook his head again. "No. We keep everything." We got into an argument, and it got pretty heated. I was acutely aware that if I walked through the checkpoint's one-way door without original documents my wife and I and our two new children would be absolutely defenseless. Thirty seconds beyond that door, I would have no way to prove to any government in the world that these children even existed, or that I had not kidnapped them. I could never enroll them in school, or get them a driver's license or health insurance. They could never travel. All of this risk occurred because the only proof that was acceptable to a government with respect to crucial facts about these children and their relationship to us, their parents, was about to be confiscated by a naive government official. Once that proof was out of my possession, if I wanted to demand redress, the first question would be a challenge about the identity of the children, and I would have no tools to respond. The situation was, in a word, terrifying. (Happy end to story: I argued long enough and with enough heat that some other employees beyond the counter took notice. A colleague eventually walked over to this man, tapped him on the shoulder, and whispered in his ear. I don't know what she said, but it caused him to relent and return the originals, and all turned out okay. I don't know this woman's name, but if I am profoundly grateful for her intervention...) <soapbox> How does this relate to personhood credentials? I think it is dangerous to build an ecosystem where proof of personhood is largely assumed to come from governments. (The academic paper on personhood creds contemplates other sources, but strongly emphasizes this assumption.) We have enough problems today with impersonal government bureaucracies grinding mercilessly on refugees and immigrants. The facts that governments attest to in such scenarios, that have the potential to result in such suffering when attestations are withheld, are "merely" citizenship/residency. If we raise the stakes further -- governments now decide who the rest of the world can/should believe is human (and thus worthy of human rights), I think we are truly in scary territory. Humans, not bureaucracies, decide humanness. Bureaucracies are derivative of humans, not the other way around. Doctors or nurses who sign birth certificates should be able to attest humanness. Tribal elders should be able to attest humanness. Government vetting processes that prove humanness should be signed by a human employee, not by the government itself, because it is the human rather than the bureaucracy that is safely definitive on this question. We should NEVER forget this. </soapbox> On Sun, Jul 20, 2025 at 3:09 PM Daniel Hardman <daniel.hardman@gmail.com<mailto:daniel.hardman@gmail.com>> wrote: I do claim (and have claimed for years, including on this mailing list and in CCG meetings) that the CCG is optimizing (unethically, unwisely) for institutional issuers (and verifiers), so I find Manu's invitation for a debate on the question intriguing. In one case -- that of so-called "personhood credentials" -- I feel that governments have absolutely NO business attesting personhood, only citizenship/residency, and that conflating these two questions is a naive and terrifying idea. I deny that governments are de-facto bases of trust about humanness (as opposed to citizenship/residency) today, and that they would/could do a good job asserting that tomorrow. However, mostly my argument about CCG focus is different from the one Manu is implying and Kyle is making, because I have no problem with a government being an issuer of a birth certificate/DL/passport, or big pharma issuing COVID certificates, or with big edu issuing educational credentials. Rather, I claim that we standardize architectures that enthrone interaction patterns that make it difficult for individuals to be issuers or verifiers, and that make it quite unlikely that these big institutions will be provers. We don't believe institutions should prove things the way individuals do, and we don't believe it's interesting for individuals to generate proof or consume it like institutions do. Individuals are not peers of institutions in our standards. Without regurgitating a super long argument here, I'll link to a couple blog posts I wrote years ago, and offer that if we want to structure a formal debate on this topic, I am happy to show up and argue my perspective. https://dhh1128.github.io/papers/bdlp.html https://dhh1128.github.io/papers/aold.html On Sun, Jul 20, 2025 at 9:45 AM Manu Sporny <msporny@digitalbazaar.com<mailto:msporny@digitalbazaar.com>> wrote: On Fri, Jul 18, 2025 at 6:44 AM Pryvit NZ <kyle@pryvit.tech<mailto:kyle@pryvit.tech>> wrote: > Will, I think it’s interesting to see your faith in institutional trust remains, because globally it’s on the decline: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/lack-of-trust-in-institutions-and-political-engagement_83351a47-en.html I don't think that is Will's point; his point is that, generally speaking, we (as a global society) have identified certain centralized institutions to do some of this credentialing and enforcement for us because it's more efficient (and safer) for it to happen that way. I don't think it's "faith"... to me, at least, it's reality. That's why issuers matter -- because none of this credentialing stuff works if you don't have issuers that people trust today. That doesn't mean that we optimize for issuers over holders... but we do realize that relevant issuers matter. We do, actively optimize for holders -- because it's their privacy and autonomy that we're trying to protect. Now, I do think that there are other technical communities that ARE optimizing primarily for issuers, but I don't think that's what's going on in the CCG (but am happy to have the debate if folks think otherwise). I'm still having a hard time understanding what you (and Christopher) mean when you say "an alternate architecture" (I did read your blog post, more on that below). For us to shift the dynamic further away from issuers, we would, as a society, need to find alternate institutions to do some of that "trust establishment" work and that sort of societal change, taken to an extreme, seems unrealistic to some of us. Now, that doesn't mean that there are certain institutions that provide centralized trust that can go away with a more decentralized solution... but society has to agree on what that new mechanism is (and we're building technology here, such as DIDs, to help provide better alternatives to things like the accidentally-centralized-and-over-used Social Security Number). Take driving, for instance. Your locality has something akin to a Department of Motor Vehicles whose job it is to test and license driver's of motor vehicles. I, personally, don't want to be involved in testing and enforcing if other people are allowed to operate such a lethal device. I certainly don't trust some of the people in my local community to make that determination... so, we've all gotten together and formed this centralized institution called a DMV to do that trust work for us. > Here's another blog post I wrote that I think provides a legitimate example to how we can shift who plays what roles within the SSI triangle to achieve a more decentralized and private means of content moderation to protect children. I hope it helps take things from the abstract to the concrete like Manu mentioned previously. > > https://kyledenhartog.com/decentralized-age-verification/ It does help quite a bit, thank you Kyle for taking the time to write the blog post and providing something concrete that we can analyze. One of the things it helped clarify for me is that by "different architecture" you seem to be saying "Let's take the primitives we have -- DIDs, VCs, etc., but put them together in a different way so that the protocols delegate responsibilities to the edge -- to the browsers, parents, and school teachers instead of the adult content and social media sites." Speaking as a parent that is stretched very thin, and who sees how thin teachers are stretched in my country -- I really dislike that idea :). Why is the burden on me, as a parent, to stop my kid from being pulled into a social media website that is designed to be addicting? :) No, I want a fence put around that thing with a "deny by default" rule around it. So, putting a "this site could be dangerous to mental health for kids under the age of 14, and honestly, it's probably dangerous for adults too." warning on the site isn't very effective. Now, I know that in your blog post, you also mention that it's really the child's web browsers job to get a credential from the operating system, which might get it from the child's guardian to make the determination to show the content to the child. If this is the case, you're shifting a massive amount of liability onto the operating systems and web browser, putting them in the position of policing content. I don't understand how that is not a really scary and massive centralization of power into the OS/browser layer (worse state than what we have now)... not to mention a massive shift in liability that the OS/browser vendors probably don't want. When a lawsuit happens, how do the OS/browser vendors prove that they checked with the guardian? Do they (invasively) subpoena the browser history from the individual? Or do they just allow the government to grab the credential log from the OS/browser? How does the browser determine what content is being shown on the website? Content can vary wildly on a social media platform, and even within a single stream. I've seen G content turn into debatably R content in a single show watched by 8 year olds. Different localities have different views on offensive content. All that to say, these reasons are often why the burden of proof is shifted to the content/product provider. If you want to sell that stuff, you have to do so responsibly -- which seems to be where society largely is these days. So, you're asking for a pretty big shift in the way society operates. The other thing that struck me with your blog post was that, while you were moving the roles around (browser becomes the verifier, operating system becomes the holder, guardian becomes the issuer), there was fundamentally no change in what the roles do. That is, I didn't see an architectural change... I saw a re-assignment of roles (issuer, holder, verifier) to different entities in the ecosystem... but at the end of the day, it was still a 3-party model with massive centralization and liability shifted to the OS/browser layer. There was also no explanation of how the guardian proves that the child is their responsibility -- birth certificate, maybe? Now we have to start issuing digital birth certificates worldwide in order to use the age-gated websites? Even if we do that, we still depend on a government institution as the root of trust. IOW, it seems to me like the architecture you're proposing is, in practice, an even more centralized system, with a much higher day-to-day burden on parents and teachers, with unworkable liability for the OS/browser vendors, that still requires centralized institutional trust (birth certificates) to work. I do, however, appreciate that the approach you're describing pushes the decision out to the edges. The benefits seem to be that centralized institutional trust (birth certificate) bootstraps the system, and once that happens, the decisioning is opaque to the centralized institution and the age-gated website (it's between the guardian and the os/browser layer) with minimal changes to the age-gated website. I think the hardest thing might be getting the OS/browser vendors to agree to take on that responsibility and liability. You'd also need a global standard for a "Guardian approval to use Website X" credential, but that is probably easy to do if the browser/OS vendors are on board. Legislation would also have to change to recognize that as a legitimate mechanism. ... or, alternatively, the website just receives an unlinkable "over 14/18" age credential under the current regime. I'm not quite seeing the downside in including centralized issuer authorities in the solution that issue unlinkable credentials containing "age over" information. There are 50+ jurisdictions among DMVs alone that issue that sort of credential in the US -- hardly centralized. In any case, one of those is far easier to achieve (both technically, politically, and from a privacy perspective) than the other, IMHO. -- manu PS: Note that I didn't really take a position on this whole "you need a digital credential to view age-gated websites" debate. It feels like a solution in search of a problem -- website porn and social media addiction was supposed to destroy my generation -- and we had NO guardrails, nor were our parents aware of the "dangers". In the meantime, it looks like we've found more effective ways to destroy civilization, so if "age-gated websites" is among our leading use cases, I suggest we're not tackling the most impactful societal problems (scaling fair access to social services, combating fraud and other societal inefficiences, providing alternatives to surveillance capitalism, combating misinformation, mitigating climate change, etc.). :) -- Manu Sporny - https://www.linkedin.com/in/manusporny/ Founder/CEO - Digital Bazaar, Inc. https://www.digitalbazaar.com/

Attachments

- image/png attachment: image001.png

Received on Saturday, 11 October 2025 07:01:50 UTC